Randomly generated

The answer is random. Purely random. My surgeons have reiterated on almost every visit that there is nothing genetic or environmental – nothing I did, nothing in my genetics or Mark’s genetics, nothing we ate, breathed, or were exposed to – absolutely nothing we did to cause these complications. There are no indicators on who will and who will not fall into that 20% of mono/di pregnancies percentile that experiences complications. If we want to place blame, the only logical place is on the placenta at conception. At conception, the vessels and tissue that would become the placenta began growing and these issues all come from a placenta that wasn’t divided equally to each twin and grew abnormally. It does help me to hear this. It helps because I can see it in the eyes of others and hear it in their tone, the unwritten “well this is what happens when older women try to have babies.” My surgeons say that’s just not true or accurate.

The exact cause of TTTS is not fully understood. However, it is known that abnormalities during division of the mother’s egg after it has been fertilized lead to the placental abnormalities that can ultimately result in twin-twin transfusion syndrome. – National Organization of Rare Disorders

https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/twin-twin-transfusion-syndrome/

To be painfully honest, I wish I’d had a life where I grew up in one home rather than attending at least 14 different schools K-12. I wish I’d had a stable nuclear family and life, gone to college as a teenager, sorted out what I wanted to do and what I could do and began my adulting fully functional. I’ll spare everyone the details, but in short my life didn’t go that way. I managed with the cards I was dealt through some very rough patches from the time I left home at age 16 through my 20s and 30s. I finally found balance in my faith and science, a path to a post-secondary education, and the love of my life rather late in life. My only options were becoming a mom over age 40 or never becoming a mom. i chose to fight the limits of reproductive biology with science becoming a mom in January 2019. As much as I wanted to be a mommy, I was wholly unprepared for the expansion of love, compassion, and critical thinking motherhood would bring. I was arrested by the joy of watching my baby become a toddler with his own personality, thoughts, and dreams. Parenthood has made me a better person, the very best revision of myself because it isn’t about me. Parenthood is an immersion in investing in others. I am thrilled to be able to provide my child with so much that I never had and desperately wanted. I cannot wait to see who he becomes with solid resources and parents who are both interested and fully committed to him. If we’re lucky, just one more time, he’ll also become a big brother and the Switzer boys (Samuel, Joshua, and Daniel) will have each other long after their mom and dad depart from this earth. And maybe just maybe, they’ll contribute to our world becoming a better place. It is all of this that I hold in my heart and pray for every day.

Aren’t twins more common with fertility treatments? Isn’t the fertility treatment to blame? Aren’t older women more likely to conceive twins?

In a word, maybe. The data just isn’t clear In fact, the data is rather muddled because the data about twins doesn’t parse easily to explicitly show trends in fraternal twins (where two separate eggs fertilized) separate from identical twins (where one egg/zygote divides to create a multiple pregnancy resulting in twins, triplets, or quads). Until recently, fertility treatments for women over age 35 was to transfer multiple eggs in hopes one would result in a confirmed pregnancy. This technique proved to be false: my fertility specialist explained that conception is largely binary. Two embryos transferred results in paternal twins 70%, and since twin pregnancies come with higher risk and women >35 and especially >40 are already a higher risk group, fertility specialist no longer recommend or support multiple embryo transfers.

According to data collected by the Centers for Disease Control, there were 133,155 twins born in the United States in 2015. That’s 33.5 per 1,000 live births, or put another way, about 3.35% of live births. There were 3,871 triplet births, 228 quadruplet births, and 24 quintuplet or higher order births. These numbers include naturally occurring multiples, along with those conceived with fertility treatment. The overall rate of multiple births increased and peaked during the 1990s but has been declining over the past decade. The percentage of triplet and higher order pregnancies has dropped 36% since 2004.

VeryWell Family 9 Things That Increase Your Chances of Having Twins (verywellfamily.com)

In the general population, identical twin pregnancies occur 0.45% of the time, or 1 in 250 births. While most multiple pregnancies conceived with fertility treatments are fraternal twins, the use of fertility treatment does increase your risk of having identical twins.

According to one study, identical twins made up 0.95% of the pregnancies conceived with treatment.11 That’s double the general population’s risk. It’s unclear why fertility treatment leads to more identical twins. One theory is that the culture embryos are placed in during IVF increases the risk of identical twinning. Another theory is that treatments using gonadotropins lead to the increased risk of identical twins.

Yet the CDC published data for 2018 doesn’t show that level of transparency.FastStats – Multiple Births (cdc.gov) source provides:

- Number of twin births: 123,536

- Number of triplet births: 3,400

- Number of quadruplet births: 115

- Number of quintuplets and other higher order births: 10

- Twin birth rate: 32.6 per 1,000 live births

- Triplet or higher order birth rate: 93.0 per 100,000 live births

Further from the NCHS Data Brief No. 351, October 2019 ” Is Twin Childbearing on the Decline? Twin Births in the United States, 2014–2018″ :Products – Data Briefs – Number 345 – August 2019 (cdc.gov)

- Following more than three decades of increases, the twin birth rate declined 4% during 2014–2018, to the lowest rate in more than a decade, 32.6 twins per 1,000 total births in 2018.

- The number of births in twin deliveries declined an average of 2% per year from 2014 through 2018, dropping to 123,536 births in 2018.

- Twin birth rates declined among mothers aged 30 and over, with the largest declines among older mothers aged 40 and over.

- The twinning rate dropped 7% among non-Hispanic white mothers from 2014 to 2018 (34.3 in 2018), but was essentially unchanged among non-Hispanic black (40.5) and Hispanic (24.4) mothers.

- Twin birth rates declined in 17 states and rose in three states.

So how can you tell if mono/di twins are on the increase or decrease if fertility treatments in the last 5-10 years went from predominantly multiple embryos transferred to single? The answer I hear from the front line is you simply can’t.

I leave you with the final Twin Fact: The U.S. twin birth rate declined 4% from 2014 to 2018. Twin birth rates declined by 10% or more for mothers in all age groups 30 and over.

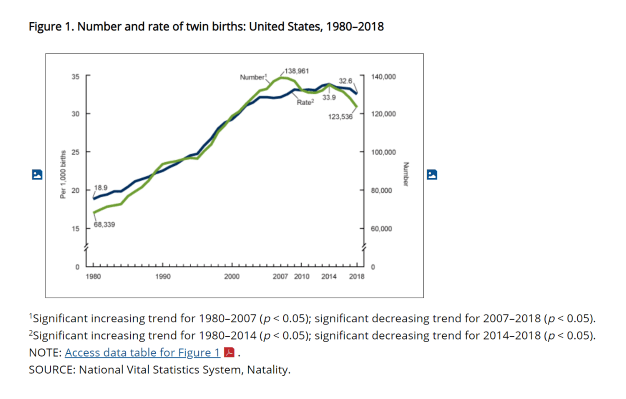

- The twin birth rate rose by an average of 2% annually from 1980 (18.9 twins per 1,000 total births) through 2003 (31.5), for a total increase of 67%. The pace of increase then slowed to less than 1% annually from 2003 through 2014 (33.9) (Figure 1).

- The twin birth rate declined by an average of 1% a year from 2014 (33.9) through 2018 (32.6) for a total decrease of 4%.

- The number of twin births more than doubled from 1980 (68,339) to the peak in 2007 (138,961), then fluctuated from 2007 to 2014 (135,336).

- The number of twins declined by an average of 2% a year from 2014 through 2018, to 123,536 twins in 2018, the lowest number reported since 2002.

The data doesn’t support that age is to blame as twin birthrates fall in all age groups 30 and over.

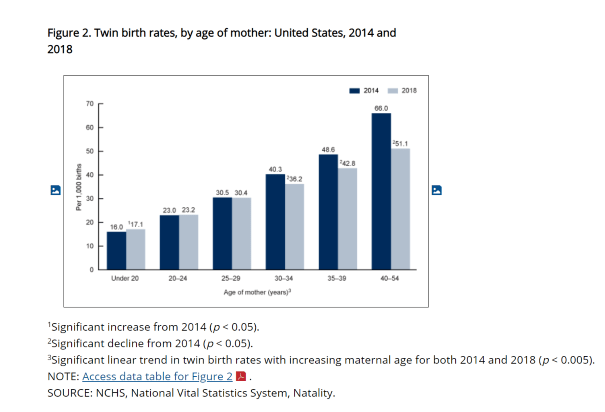

- Twin birth rates declined for mothers in all age groups 30 and over; the rate fell by 10% for women aged 30–34 (from 40.3 per 1,000 total births to 36.2), 12% for women aged 35–39 (from 48.6 to 42.8) and 23% for women aged 40 and over (from 66.0 to 51.1) (Figure 2).

- Twin birth rates were essentially the same between 2014 and 2018 among women in their twenties (from 23.0 to 23.2 for women aged 20–24, and from 30.5 to 30.4 for women aged 25–29), but increased for mothers under age 20, from 16.0 to 17.1.

- In 2018 as in 2014, twinning rates increased with advancing maternal age. For both years, mothers aged 30–39 were more than twice as likely, and mothers aged 40 and over were three times as likely to have a twin birth, compared with their counterparts under age 20.